This article was originally posted on November 28, 2023. Read the article the SIPA website at https://www.sipa.columbia.edu/news/saving-journalism

Anya Schiffrin is the director of the Technology, Media, and Communications specialization at Columbia SIPA. She prepared the following report on the recent Saving Journalism conference.

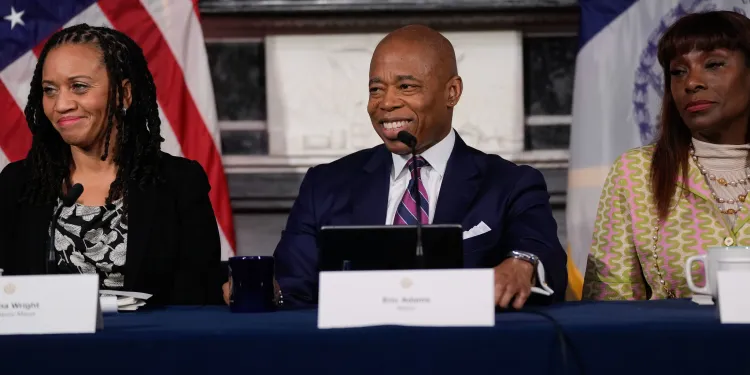

Using city advertisements to support local news — a policy put into place by then Mayor Bill de Blasio — has, over the last four fiscal years, funneled $67 million into New York City’s ethnic and community media, de Blasio said during a recent appearance at Columbia.

His remarks came at the third annual Saving Journalism conference, held at Columbia University’s Forum on November 3. The one-day event gathered donors, scholars, and practitioners to discuss policy interventions around the world that help support quality journalism. It was organized and sponsored by SIPA’s Technology, Media, and Communications specialization in partnership with the Centre for Media Technology and Democracy at the Max Bell School of Public Policy at McGill University and Columbia World Projects.

The need for funding for local news is a global problem, one that worsened in New York when many local businesses went out of business and stopped advertising in local news outlets.

“Any level of government has such extraordinary spending power and economic impact, but it’s rarely thought of as a tool for changing society in and of itself.”

— Bill de Blasio, former NYC mayor

The conference’s first panel discussed a New York City solution —the 2019 executive order, signed by de Blasio, that channeled local government advertising to support local news. The policy has been successful in New York largely due to the efforts of Jose Bayona, executive director of the Mayor’s Office of Ethnic and Community Media and Graciela Mochkofsky, the dean of the Newmark Journalism School at CUNY, both of whom have put enormous efforts into working with local news outlets and government agencies that place advertising.

“Political will is what made this happen,” Bayona said.

De Blasio explained how he embraced the idea when it was first proposed and spoke of the secondary efforts that government spending can have — especially in a place like New York, where the operating budget during his tenure was some $100 billion a year.

“Any level of government has such extraordinary spending power and economic impact, but it’s rarely thought of as a tool for changing society in and of itself,” de Blasio said. “We think of the government norm is you spend a whole bunch of money to procure a good or a service to serve people. And that’s good, that’s fine. And of course, we should do that with integrity, we should get the lowest bid whenever possible, all those things. But there’s a second level that is often missed, which is that the amount of money we’re talking about can have a seismic impact in other ways.”

SIPA’s involvement in the policy discussion about using government advertising to support news dates to 2010, when a team of SIPA students worked with me on a Capstone report for the government of Bhutan about the risks of using government advertising to support news. The country’s monarch, King Jigme Khesar, wanted to support the media as part of Bhutan’s transition to democracy; the country had begun subsidizing local print outlets, many with low circulation. Our student team wrote up a 120-page report with case studies of successes and failures in Argentina, Canada, Colombia, India, South Africa, Sweden, and the UK, and made recommendations as to how to avoid common pitfalls. Two of our students flew to Bhutan to present their findings and the government of Bhutan changed their policies accordingly.

Since then we’ve kept discussing the risks of government advertising in conferences we’ve organized and in three volumes we’ve edited on the problem of media capture—about the risks of soft pressures end up influencing editorial processes.

However, in the United States the success of New York City’s efforts has encouraged other cities to follow suit, said panelist Steve Waldman, founder of the nonpartisan Rebuild Local News Coalition.

As New York’s policy has inspired other governments around the United States — including in Chicago, Connecticut, and California — we helped the Rebuild Local News Coalition and CUNY’s Advertising Boost Initiative, which recently launched a media toolkit for other cities that want to emulate New York’s success. Specifically, we contributed some insights based on our research of international cases. As part of the planning meeting in April 2023, we invited Australian professor Sally Young (who we had cited in our 2010 report) to come and update us on where things stand in her country. Jonathan Rose of Canada also came; it was exciting to finally meet in person the people we’d quoted in 2012.

“Part of the reason why this is such a popular idea is it doesn’t involve new spending. It’s just saying, you’re already spending this money, you already have an obligation to get the money out into the community, but it’s not being done in an equitable way or in a way that can really get down to community organizations”, said the Rebuild Local News Coalition’s Waldman.

This success of the New York City executive order is in large part due to the efforts of Mochkofsky and members of her CUNY team, who helped implement the executive order by working closely with local outlets, many of which had never received city advertising before and didn’t have relationships with the ad buyers who place the adverts. They set up an application process for news outlets and the program channeled funds to outlets, such as the Haitian Times, which had never received city advertising before. The measure helped the community outlets that cover local news vital to the city.

“I really, really want to urge people to spread the gospel of this idea and see where it can be achieved,” de Blasio said.